Syrian Refugee Students’ Reflections of Space in Jordan’s Double-Shift Schools

After experiencing disruption, pain, and unimaginable loss, Syrian children arrived in Jordan and desperately hoped to regain their childhood and be students, friends, and aspiring individuals once more. Today, nearly a decade has passed since Syrian refugees were first forcibly displaced into neighboring nations in the Middle East.

Governments in Lebanon and Jordan have developed official national strategies, successively renewing their commitments to the needs of refugees as well as their most vulnerable national communities. One key approach to increasing educational access for refugees within strained resources has been the double shift system, which uses the same school building for two shifts – the morning shift for national communities and the afternoon for Syrian refugees.

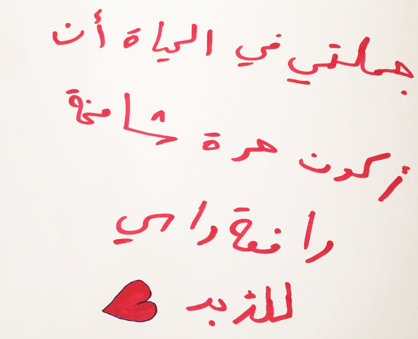

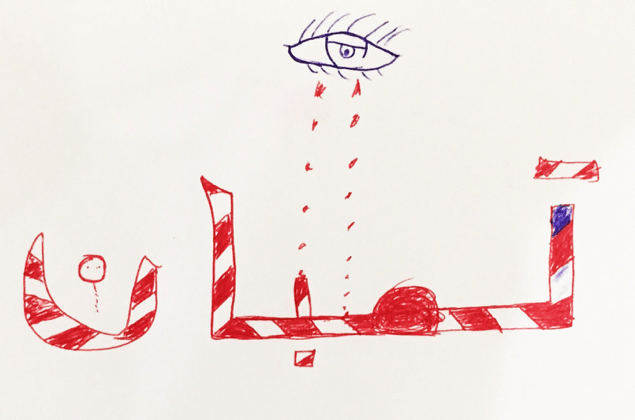

Yet, with the passing of years, this separation between the two communities in double shifts in schools has raised important considerations about students’ abilities to belong, experience stability, and build hope. I spoke to 78 Syrian refugee students, aged 13-16, across four schools in Jordan, and asked them to reflect on their education in the second shift. Here is what I learned from students’ experiences in schools.

Segregated schools create fear, targeting, and labelling

As morning shifts end, Syrian refugees make their ways to school to begin their learning around noon. Syrians in Jordan also attend school on Saturdays to compensate for lost learning. Syrian students feel easily targeted, and they are unable to regain normalcy. This targeting has had huge implications on the violence, bullying, and harassment that Syrian students face both inside and outside of their schools, which has also been linked to drop out. Students in my study frequently talked about how they wished not to be visibly refugees, but to be respected and known for their individuality.

“Everyone can easily identify us as Syrian refugees. They see a student coming to school at 12 or leaving school at 4 PM and they would know we’re Syrian. Last Saturday, I came to school with a cab and even the cab driver said ‘School on Saturday? You must be a Syrian then.”

— Sara, female, 15

“They only know me as refugee, they don’t know my name. It’s an ugly word.”

— Aziz, male, 16

high.” — Roula, female, 16

Inclusive schools are important for compassion, friendship, belonging to a new home, and space

Most participating students in my study stated that they did not know a single Jordanian, despite years of living in the nation. Students reported experiencing only negative interactions with Jordanians, talking about how they felt lonely, isolated, and rejected, separated from old friends and extended family and unable to engage within their new communities. Students’ low sense of well-being and isolation reflectsthe importance of safe and transformative spaces that would allow Jordanians and Syrians to learn together, to build understanding, compassion, and unity.

“I wish there were more and more people for us to meet.”

— Kareem, male, 15

“I want to see more people, meet them and learn from them. It would make me very happy and it would encourage me to study and think about the future.”

— Saeed, male, 15

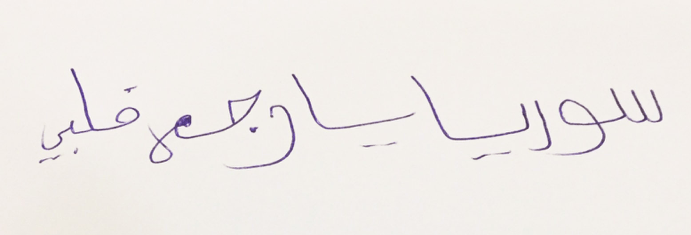

Welcoming communities are important for healing and hope

To many Syrian children and youth, Jordan has become a second home. Yet their thoughts about the future echo the contradictions they find in experiences in both Jordan and Syria. Many Syrian refugee students dreamt of returning to Syria, but they also wished to find stability, dignity, and positive connections within their new spaces in Jordan. Students’ limited exposure to welcoming and inclusive environments reinforced their painful memories and traumatic experiences, preventing them from healing and moving on.

“I think about my country every day but when my dad says, ‘let’s go back to Syria’, I hesitate and feel conflicted. I grew up here. I was eight when we left Syria and I’ve studied here for four years.”

— Basheer, male, 14

“I think a lot about what I went through in Syria, but I think about it most when someone in Jordan upsets me. If they had gone through what we went through, they wouldn’t talk to us like this.”

— Rima, female, 16

There is hope and power in even the smallest forms of positive exchanges

While many students described a sense of pain, isolation, and rejection, many still held on to the value of education and its ability to carry hope for the future and opportunities. At one school, students had recently joined a program that allowed them to meet Jordanians once a week in school, where they played and learned together. Teachers noticed that this infrequent integration reduced the level of violence around schools, and many students felt reignited by the possibilities of new friendships. The smallest examples of true integration show the potential of relationships in education that can support communities to heal.

“I want to only think about the future. I want to only focus on what I want to become.”

— Sima, female, 15

“I do want to go to school with Jordanians. We have this program here at school and the Jordanians were very nice to us.”

— Talia, female, 15

Read the Arabic version here.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Hiba Salem is a Research Associate at the University of Cambridge. Her work specializes in education in contexts of displacement in the Middle East, and she focuses on examining the effects of educational spaces on well-being, social cohesion, and belonging. Hiba has also been involved in numerous projects looking at the field of education in emergencies more globally.

Follow Hiba on Twitter (@hiba_salem) and hear more about her work through her recent Tedx Talk and other sources. Hiba is currently in the process of publishing her PhD findings in several upcoming papers under review.